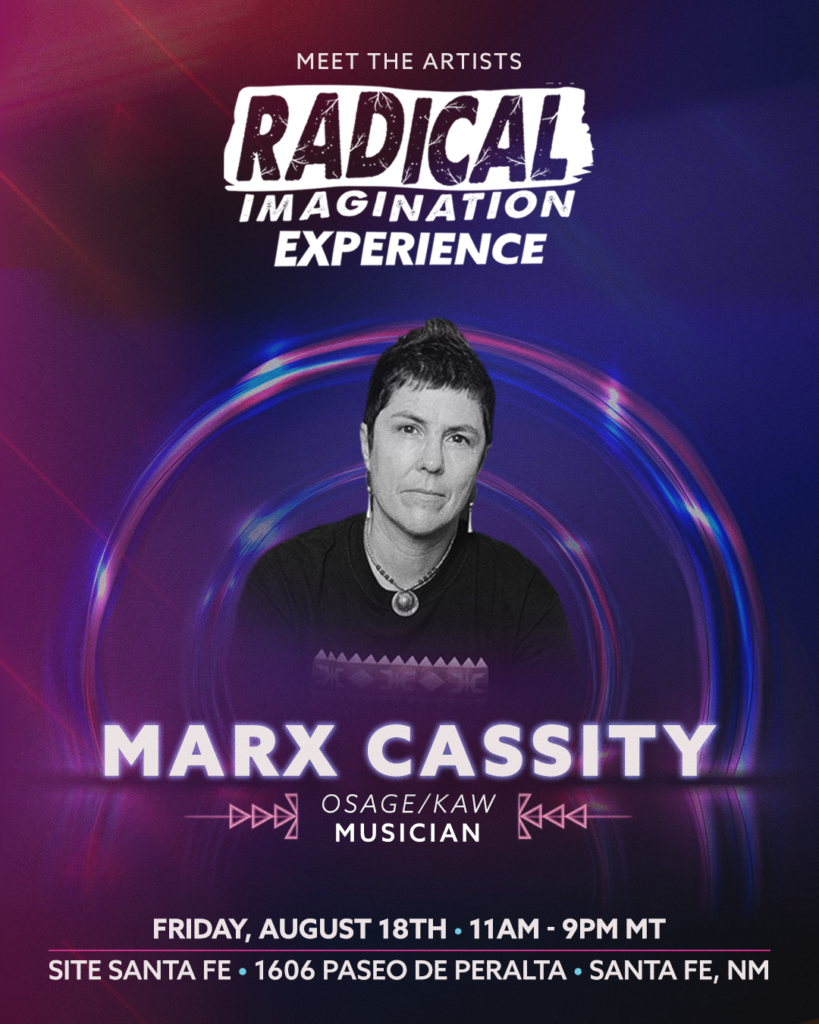

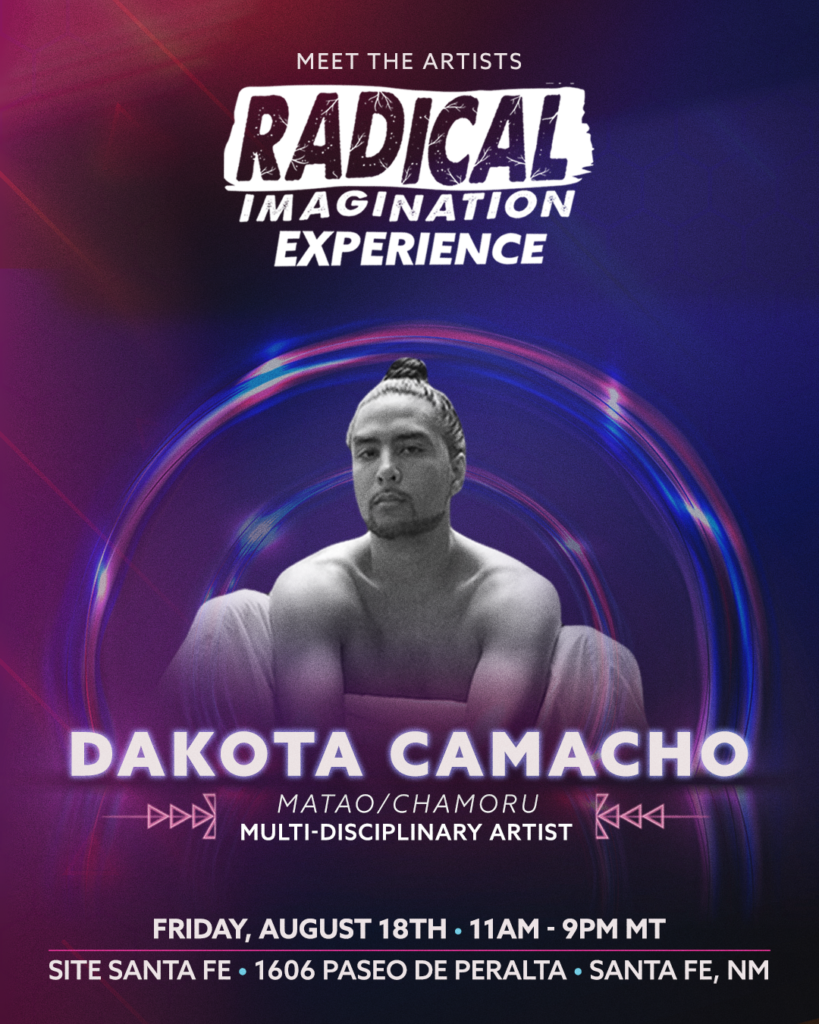

Often we envision performing artists as those whose sole aspiration is to entertain us, but there is a medicine living and breathing in the movements, words, prayers and intentions set forth in this artform. Medicine that validates our experiences, provides comfort, invites celebration and incites joy. Three performing artists providing this medicine are Marx Cassity – Osage Musician, Dakota Camacho – Matao/CHamoru Multi-Disciplinary artist and Jordan Brien aka Mic Jordan – Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Musician and Creative Designer.

Marx and Dakota are recipients of NDN Collective’s Radical Imagination Grant, which supports 10 Indigenous artists every year as they create and expand on unique expressions of a radically imagined, more just and equitable future through community-based cultural expressions that propose solutions to our most challenging societal problems. Jordan Brien is the current Creative Producer at NDN Collective and spent years as a musician traveling Indian Country performing and speaking to Native youth.

The 2021 Radical Imagination Artist and Storyteller Cohort will join in community for the Radical Imagination Experience – The Art of Creative Resistance and Change,” a free, immersive community event that will take place on August 18th in Santa Fe, New Mexico leading up to the SWAIA Indian Market weekend. Jackie is one of two phenomenal graphic illustrators who will be presenting their art at the Radical Imagination Experience event, connecting with attendees through visual art-making activities and engaging in panel discussions alongside other cohort artists.

In anticipation of the event, we sat down and had conversations with Marx, Dakota and Mic Jordan, discussing their projects, artistic vision, gearing up for the event in Santa Fe, and so much more.

Here’s what they had to say:

As an Indigenous artist, you blend genres of music together, often bridging Indigenous sounds (traditional singing) and non-Indigenous sounds (rock/electronic). What is it like to bring these different styles of music together?

Marx Cassity is a musician and enrolled citizen of the Osage Nation with Kaw, Saponi, and Susquehannock as well as French, Scottish-Irish, Irish, English, and German heritage. They deliver inspired folk-rock-electronic songs with Native nuances, that speak to overcoming hardship through resilience, in connection to nature, humor, love, compassion, spirituality, and heritage.

MARX: From the very beginning here, honor Buffy Sainte-Marie. To witness her career, starting in the sixties with giving Joni Mitchell her first gig. She navigated as an Indigenous person, taking part in civil rights and having her career being heavily impacted by the US government blackballing her.

For her to stay so creative in bringing it. She was the first artist to have synthesizer on an album in 1964. First artist, Indigenous artist, is Buffy Sainte-Marie, who departed from straight up folk music with her guitar and into synthesized electronic music and then, moving through time and history, just this amazing rock, electronic, folk with Native nuance lyrics, Native nuance singing, layered singing and different styles.

The nuances lyrically, thematically and sound wise is just incredible. She just retired this week from performance and I’m really feeling it. She’s 82 and I’m just like, “wow.” She said she’s not going to tour anymore, and I’m like damn she’s 82, like wow, we’re just lucky she has still been touring. So how is that for me? I’m inspired by her. It’s an ongoing inspiration.

I wrote passionately to NDN Collective and said, I want to take all my lived experiences as a therapist, an Indigiqueer person and an artist and do something.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

Also, having lived through the eighties in Oklahoma and coming out, living on the reservation and living within conservatism and how my people and my family were impacted by colonization. They lived in a lot of fear whenever I came out as queer at the time. I was a tomboy growing up on the reservation, and everybody was fine with that. They tagged me [as] that and I loved it. I could be a tomboy. But when I went to college, being a piano major and coming out as a butch, lesbian or trans masculine person, whoa, that did not go as well. In the eighties, in the height of the AIDS crisis in Oklahoma. They called it the gay plague.

I was at the first gay pride parade [in Oklahoma] in 1989. [There was] about five hundred of us who were being so impacted by death in our community that we decided to march, and that’s how Pride started. It’s very different now. Pride is full of AT&T and Google. Part of the way that I survived that time, losing my attachment with my family, was by being in the city, until my family grew and evolved over time and are total allies now. All of my family.

[While in the city]I survived in the bars. I was in the gay clubs and this is where Madonna, Eurythmics, Prince, Bowie, Whitney Houston, and Depeche Mode played. All this electronic soul vibe. Dance music was my church. That was my survival. But always, of course, still coming home tenderly, vulnerably. Coming home and going to Native events and Pow Wow and the American church, when I got a little older. The music there, also the drum and the nuances and the singing nuances, that Buffy does so well.

It was Wah’kon-Tah, our word for Creator and God. It translates as the great mystery in Osage. Wakonda, no gender to that. It’s a great mystery and Creator, and I feel like it came through the lightning and told me.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

To blend this, the way I’m blending it now, because this album is a launch out of folk rock into folk, rock, electronic. I brought in a Annie Lennox, Eurythmics kind of vibe, synthesizer, along with folk guitar, acoustic guitar and piano. This was my return to piano because when I came out, I dropped out of piano as a piano major and my life was so, kind of, fractured. I moved around a lot and I didn’t have a piano, I had a guitar and so I wrote on guitar. But this is the first time in my life I’ve had more stability and I returned to piano and wrote this album on piano. It really was healing for [the] younger me, who came out and lost all that. It was a return.

Marx’s Radical Imagination project entailed making a 10-song album and music video about Two-Spirit belonging and its connection to decolonization.

It was almost like I was singing these songs for younger me as well as the youth whoI know are impacted so much by colonization around sexuality and gender. It’s just super great to know, to return and to have the space, time and the funding from NDN Collective to take my time. It’s evolved me as an artist. It’s evolved me as a person. It’s evolved me all the way to moving back to Oklahoma. That’s this project,singing this way, and these themes. This is an entire album themed in Two Spirit resilience. Every single song. It’s been quite the journey.

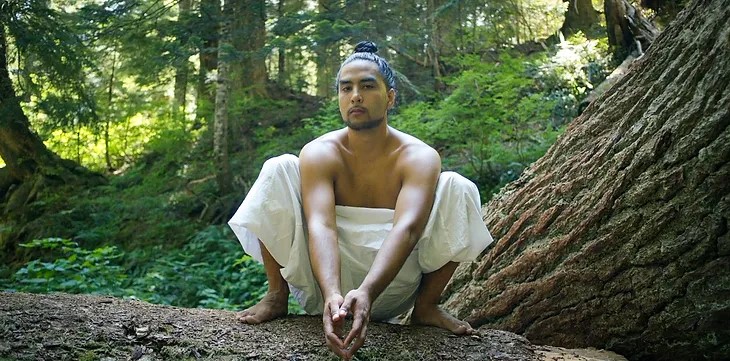

Dakota Camacho is a multi-disciplinary artist born & raised in Coast Salish Territory, currently residing in Guam, who creates indigenizing processes by weaving languages of altar-making, movement, film, music, and prayer.

DAKOTA: The first introduction that I had to my culture’s music was through rock and country music. This is very touristy music. One song that I’m always quoting, regarding the people that I grew up [with], goes [like this], “Guam USA is where I come from, and that’s where I’m supposed to be, enjoying the land all along the beach under the coconut tree…Guam is good. Guam is hot. Guam is just a little spot. It’s a beautiful island that you’ve never seen where America’s day begins.”

That was my first exposure to cultural music. At the time we also had songs that we sang, at funerals. But I didn’t think about that as cultural music. The song that I just sang is one of the songs that my family had a cultural dance group to. Part of the reason I’m saying that is because even my introduction to Indigenous cultural expression was already tied up in the story of the globalization of Black music.

When I was a teenager, I started to fall in love with hip hop. Part of that was that there’s a traditional form of poetry, which I now am a very baby practitioner of, but that form is called Mali’e’ or Kantan CHamurita . It’s rhyming. It’s got repetitive aspects to it. It’s allegorical, metaphorical. You’re really good at it if you’re skilled in wordplay. When I found out about this art form I wasn’t a speaker of the language at that time. But I did resonate with the technology.

The thing that is the clearest there for me is that creativity is an opportunity to commune with my ancestors, as an extension of my ancestors, the Creator.

Dakota Camacho (Matao/Chamoru)

The technology is the techniques of the practice. Part of that was through doing rap battles with my friends in middle school. Around that time, I also got introduced to hip hop by this group called Abyssinian Creole, which is an Ethiopian and Haitian rap duo. I learned how to rap from them. I learned about hip hop as a tool of community liberation and some of the principles of a lot of liberation focused forms, which is that we tell our own stories. A big part of hip hop is bringing your own personal voice through.

I had a lot of questions for myself, like, what is the sound of my people?I had a really interesting upbringing in the sense that I started off with my culture around me, and then I didn’t have it around me. I was around all of these different cultural forms. I spent some time hanging out with Chicanos and playing son jarocho music and it was beautiful because all of these different cultural art forms taught me about myself. I was writing yesterday about how I think hip hop was a place that I learned how to tap into my ancestral knowing. It was a place that taught me how to put myself in the flow of the Creator. Learning my own cultural art, like art forms and chanting, for example.

Another interesting thing about this question is that we have lost a lot of our culture. What we understand now about chanting, like cultural dance and chant, all of that was created in the eighties onward. That’s not to say that it’s not of us, but it is to say that there isn’t necessarily one continuous line of practice. That has also taught me a lot about what the role of tradition [is].What does tradition do? How does it do what it does? Why is that? A lot of my curiosity has been around how different traditional art forms work and why? What’s the worldview that they’re made within?

One thing that I like to say about my process is that when I am in the clearest alignment with myself, then my writing is more a record of what I’m listening to. I’m listening for the voices of my ancestors. I’m listening for the sounds.

Dakota Camacho (Matao/Chamoru)

When it comes to the blending of genre in music, for me, it’s not necessarily something that is intentional. It is intentional because I’m intentionally expressing me, but it’s not like, “oh, I’m going to blend hip hop and my tradition to make this cool new thing.” It’s more like I’m in the process of discovering myself. I’m in the process of discovering my culture. I’m in the process of discovering what’s true about us as Matao people, and creating is a way that I’m healing from oppression, colonization and from the weight of all these questions.

My music and my creativity is one method of doing that work. When I think about my music, especially music I’ve been creating lately, I’m more and more curious about what is the sound that is unique to me? What is the sound that’s unique to my people? I believe that there’s an inherently healing vibration when you’re in that alignment.

For me, participating in these different cultural art forms is like being in continuity with them. When I say different, I mean non-indigenous to me. For me, it’s also a way of acknowledging the impact that these communities have had on me or my family. It’s a way of honoring the relationships that I and we have made.

That’s something that’s becoming more and more important to me to be really clear about. It’s also relational because it’s honoring that a part of my heritage around growing up outside of my homeland, and [that has] afforded me this great gift of being in relationship to all of these different communities.

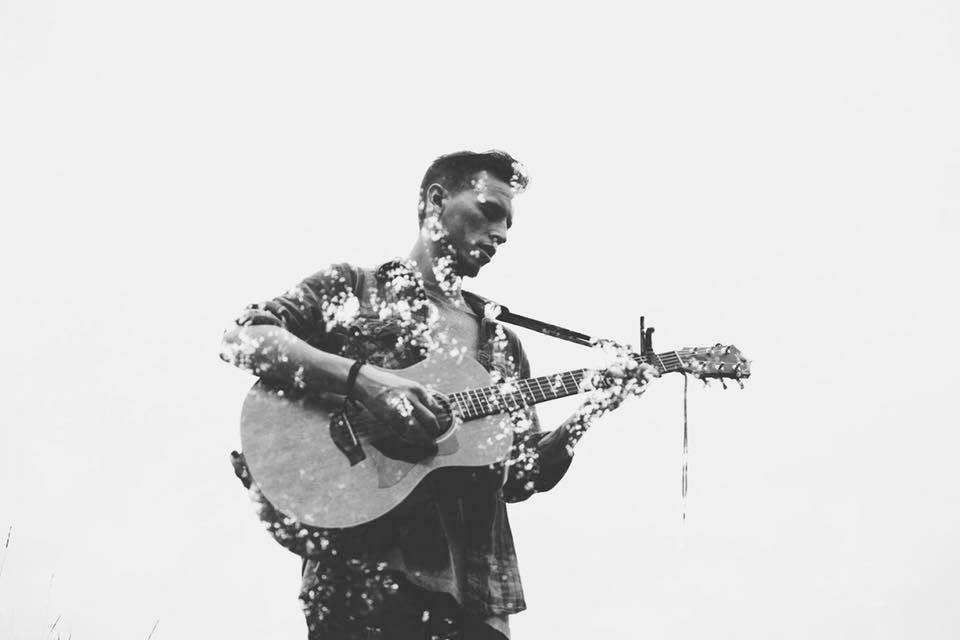

Jordan Brien is a musician and a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe Tribe in North Dakota. He spent years as a musician traveling Indian Country performing and speaking to Native youth. He is currently the Creative Director at NDN Collective and carries years of experience as a graphic design professional, coveting a wide range of expertise in creating visual communication for digital media marketing, including websites, online advertisements, social media campaigns, and brand identity.

JORDAN: With music creation, I’m able to show up in two different ways: as a producer, finding all sorts of sounds and blending them all into a mix and also as a songwriter and music producer, I’ve been able to just take a lot of music that comes from powwows and traditional music and blending them into a modern context. But definitely with a hip hop vibe to it. With my upbringing, the beat is so important. I write to a beat, and growing up on the powwow circuit as a dancer, I was a fancy dancer, those beats were just everything. I’ve been able to create from a production side, but from my own production side of things that I’ve created with blending the sounds of our traditional music has been mostly for just our work here at NDN, our soundtrack music.

But as far as my own music, I produce a lot of my tracks. But I think for that, there’s less production in that work but more storytelling. And from my upbringing of what was introduced to me at such a young age, I was really hooked on songwriting. I was very influenced by artists like Neil Young and Bob Dylan and also Tupac and definitely A Tribe Called Quest. There’s so many more. So my music is a blend of all of that.

I manifested this ever since I was a little kid, when I was super lost and I didn’t have role models. I didn’t have dads who were there or uncles. I had posters of hip hop and music. I had Michael Jordan posters on the wall. I had this little boombox that saved my life. It was my way of surviving.

Jordan Brien AKA Mic Jordan (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe)

I guess I classify myself as a hip hop artist, but my music is definitely songwriter music. And I think in storytelling music, our people were the best storytellers ever, I’ve been able to blend that in, as much as possible. The stories that I carry, they’re very relative to our people because that’s what I grew up on. That’s how I’ve been able to blend all these different sounds from hip hop to classic rock to all of that stuff. Even movement music that we never knew was movement music until we really realized a lot of what Tupac was doing, definitely standing up [against] police brutality and speaking up against all that stuff. I get to do that in both realms as a producer and also as a songwriter.

I listen to Bob Dylan and Neil Young. The architecture of their storytelling as they can really contextualize what they’re trying to say. That landed a little bit on me in a way, but nothing landed on me like hip hop music did. Especially what they were sharing those stories of struggle, [they] were very powerful to me as a young kid. I think that’s what really stuck with me. This blend of contextualizing moments and things that were happening and then also like struggle. That’s the blend right there and I think I’ve been able to do that with my music a lot.

Music has to hit me spiritually. It depends on where I’m at in my life. I can’t just grab the guitar and make something, it has to come visit me, it has to come visit my spirit. A lot of my most powerful songs were songs that I couldn’t even get through. I had so much emotion that I carried when I was writing it, that I knew it was something so powerful. As much as I’d like to call it a talent, it really comes down to moments of listening to your heart. I definitely feel it a lot when I’m writing things , I’m not alone. It’s like in ceremony, right?

Ceremony is not easy, you got to welcome things into your sacred space. Usually you’re thinking about yourself, right? And then on the third door it’s really hard because you’re not just praying for you. Or in my case, I’m never just writing for me. The fourth door is the editing part where you go back and you edit your songs and that’s when Hau Mitakuyse, the door is open [and] all my relatives are coming in. You got that little breeze in and then you get out and there’s that fresh air and that’s that music.

Where do you draw your inspiration from and what prompts your creative process?

MARX: Musically, I have lots of influences from a lot of different kinds of music. I was trained classically. I was lucky enough to live in a town, well, lucky or not lucky, I lived in Ponca City, a town that had people from all around the world because it was the headquarters of Conoco oil. There were oil executive offices here when I was growing up, they’re not here now, but they were here back then, and so, of course, there was a lot of funding in the school system, including the arts.

Osage themselves are known artists, you know, with Maria Tallchief and the arts. My great grandmother played piano. She’s an original artist and came from that class difference of having oil money headright. They took that and educated themselves and did a lot around music and art, so that is also in my family. But the city also, you know, fortunately at the time I had that [too]. So, classical training all the way to high school, all the way to college. I was a piano major, classical piano major in college, but I also love rock and roll.

Part of the way I survived through some of the challenges that Native families have around mental health, substances and alcohol and as a kid, living in conservatism and a being queer kid, tomboy kid, being real different, was going in my room and listening to all the seventies [and] eighties [music] – Queen, Billie Joel, the Woodstock album, Janis Joplin, Pat Benatar.

I was in there like air guitaring and then started picking up guitars and just making sounds and different things. All that influence. I realized more recently that I was basically training in the folk, rock, electronic world right there for hours and hours and hours, deep listening and emulating. Then the classical training, too. I’m really lucky to have all that.

As far as writing, I think, again, when I was living in Oklahoma City after coming out, I dropped out of music school and was pretty lost, but I had like these amazing musicians in Oklahoma City, like Peggy Johnson, who was this lesbian folk singer who gave me my first opportunity to come and play on stage. I was playing cover songs, the Indigo Girls and Ani DiFranco and stuff. She’s was like, “hey, kid, come on, you know?” Letting me get my performance chops and just play my cover songs.

I didn’t really start writing until I was 30. I left Oklahoma in 1997 and moved to Boulder, Colorado and found this amazing consciousness community there, full of artists and healers and teachers from around the world. Boulder is really great. That’s when I was exposed to more performing songwriters and that scene. I ended up with a radio show. I was a radio host featuring female artists and songwriters and then sort of traveling all around.

I made an album and I guess, at that time it was kind of like Melissa Etheridge and Ani DiFranco. When they first came out with their albums, they weren’t out of the closet yet. They all started coming out in the nineties. It was really great. By the time I made it to Boulder in 98, 97, you know, I was starting to come out too and write about my experiences. I think thematically, even lyrically, I was writing and doing some art therapy with myself, you know?

Like I said, my mission was to make an album that I like to hear and that if one person hears it and stays alive, mission accomplished. The guides are saying it’s bigger than that so hold steady and put in the work.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

I was a rep here at the Oklahoma City bombing. I had gone to nursing school, to work in the AIDS crisis, and I was an E.R. nurse and ended up downtown when the building blew up. I went right to the building and I wrote a song. That was one of the first songs I wrote.

When I moved to Boulder I was just kind of working through trauma. I think the themes for me are a lot of, here’s the painful stuff and here’s some teachings or some inspiration or some nature or some trees or some kind of mantra. I was studying teachers from all around the world, and I would just write about applying that to what I was going through. I’d bring in the guitar and start to write, and here they come, you know?

Then I’d do a little crafting. I would go hang out with other songwriters and talk about how they would write, but not a whole lot. I started hanging out with people who actually were doing this in the world as professionals. Wendy Wu was one person in Colorado who really helped me, saw me and valued what I was doing and encouraged me to come out and play on stage. That’s a craft too, that I honed. I went out to California to do even more of that.

DAKOTA: The thing that is the clearest there for me is that creativity is an opportunity to commune with my ancestors, as an extension of my ancestors, the Creator. The source of creation, the source of creativity, for me, has always been a process of stilling my mind. One thing that I like to say about my process is that when I am in the clearest alignment with myself, then my writing is more a record of what I’m listening to. I’m listening for the voices of my ancestors. I’m listening for the sounds.

As I’ve developed as an artist, how I listen has shifted and transformed and deepened the techniques and the practices that I use. Everything from intentional breathing to praying and asking, to making certain kinds of offerings, to preparing my mind and my body, the application of particular medicines.

It also depends on what it is that I’m creating. Music is one aspect of what I do now so the creative process also depends on what is being created and why. The core of it all for me, when I’m in alignment with myself, is prayer. Part of the practice of being a creative is to align.

I was thinking about this this morning when I was at my job where I was like, I feel like I used to believe in possibility more easily. I’ve only been working at this 8 to 5 for four or five months and I caught myself as I was coming out of dreamland. Even just thinking about somebody’s capacity to transform. I was like, “oh no, they can’t.” Then I was like, wait, the Dakota of five months ago didn’t believe that. The Dakota five months ago believed that anything was possible.

I think about my work as Indigenous education. I really try to set it up for people. We are all actively creating this moment. Decide how you want to enter and engage and keep deciding.

Dakota Camacho (Matao/Chamoru)

That’s also what I mean about alignment. It’s interesting because alignment is not something you achieve and then you’re there. It’s a constant process to me. That has been the purpose of creativity in my life, to learn more about myself. What do I really believe? What feels true and good? Most of the time it’s a feeling. It just feels right, you know? Another piece of this process is thinking about if I’m not aligned, if I’m not ready as a vessel. It’s something I don’t necessarily think about all the time, but it’s true.

Sometimes that is being on the land. Sometimes that is being in a ceremony with people in different places, with myself and/or with others. I’m hearing the voice of an elder be like, “don’t have favorites.” But you know what? Sometimes when I think about a piece that really moves me, that’s come through me, I’m like, “well, that actually came from a moment, from an energy that was before that moment,” right? The writing is a record of that too. So, some of the process is also being in community, being in the process of communion.

JORDAN: Gosh, it’s a little bit tougher nowadays. Holding our work and also my responsibility as a father. To write music is such a luxury. It is an absolute luxury. And it adds the pressure that you have just this amount of time. It’s been a challenge for me to create new music. But I’ll say for music that I have created, I definitely had more time, but it starts with my favorite piece of equipment in the tool belt of my writing music – my guitar.

I’ve been playing guitar for probably close to 20 years and I could be anywhere in the world, stranded on a desert island or by myself. But if I had my guitar, I would be all right for a while. My music always starts, every single song that I’ve ever written, starts off on an acoustic. I write on an acoustic and most of the stuff that I write, there’s a lot of emotion to it. It could even be the happiest thing, butit’s a real sad song on a guitar.

Sound engineering wise, our voices are on the same EQ as guitars. hat’s why people are like, “Oh, I love how you sound on acoustic.” Well, that’s because our voices are so synced with guitars. There’s a certain sound that I come up with, a certain rhythm. I find it in acoustic and take that acoustic song, a demo, and then I make it [into] a hip hop song. An example of this was [when] I wrote “Music Saved Me” on acoustic guitar.” “Music Saved Me” is a song about music literally saving my life. I talk about how I struggled with just some things and music really just saved my life. It’s a really sad song on acoustic, but if you heard the hip hop version, it is such a positive song, but real dark.

A lot of my music I wrote for me, but I [also] wrote it for our youth to hear. [Music Saved My Life] wasn’t fully written and we won the Battle of the Bands in college. That was my closing song. It was so hype and I was like, “Oh my gosh, I got to finish this song. It’s so powerful.” My music creation process, it definitely starts with an acoustic guitar, [and] unpacking that emotion.

You’ll be performing at the Radical Imagination Experience event in Santa Fe. What kind of experience do you hope to bring to the stage and platform?

MARX: Gosh, I feel like it’s a celebration. It’s a time for us all to get together, this whole cohort. I got to be in person in New York last year, but we’ve mostly been online, so to be in the same room together and celebrate all the different types of artists throughout the day is exciting. I’m also going to drop my visual art on that day of those motion portraits, on a reel and I’m going to do an exhibit where I’m inviting Two Spirit people, Inidigiqueer people, to come during the day.

To exhibit the motion portraits in with all the other artists and what they’re bringing and then the performance at night. I showed that video at Grantmakers in the Arts, but I had to keep them from putting it online. This is my first public showing. I’ve shown the video around, you know, parties at my living room or whatever, but this is it. This is the premiere and it’s almost a year later than what I had planned. It’s been a long journey holding onto this, but I’ve been holding onto it so I could premiere it properly.

is the first time in my life I’ve had more stability and I returned to piano and wrote this album on piano. It really was healing for [the] younger me, who came out and lost all that. It was a return.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

I keep getting slowed down as another form of the version of the guidance has been, it’s not time yet. It’s not time yet. I’m like, I need hip surgery? Why? Wait. I’m moving to Oklahoma? Wait, why? You know, and it’s like, not time yet. Just be at the pace that it unfolds, right?

I get to be in a room full of people and premiere this on a large screen. This entity and all those people in the video, some of them, my dear friends, some are from the Portland All Nations Canoe Family. Most of the people in that living room scene I had never met before that day. I just put out the call to the Native community of Portland and Renea Perry, who’s the head of the Portland All Nations canoe family brought fresh cut salmon for the entire cast and crew. Just brought it to my house.

These amazing queer, Indigiqueer Native folks just showed up in Portland and then my friends. My friend Claudia Cuentas, who’s a Peruvian, who’s a healer and a singer and a therapist, she came and created that ceremonial set design that’s in the circle of healing amongst the community.

To screen this and be with people at this place and know it’s the launch. It’s also launching online that day. This is the first time it will go out to the world. It was supposed to go out last October. I’m just like, yes, it’s happening! [laughs] Just hit play, please and I’m going to sit back.

Frank Waln, Mic Jordan, Dakota Camacho and I are going to get there a day early and kind of collaborate. I’ll sing at least one more song. I think I’m going to sing ‘2S Sacred’. ‘2S Sacred’ is this love song to the ancestors and trancestors that I wrote and I’ll play some kind of piano. I have a piano there, and we’re going to collaborate a little bit. So just to get to sing the songs to people. They’re not released yet. They’re going to be slowly released over time, all the way to October and November.

Just a celebration, that’s what I’m looking forward to. Getting to reveal the art like so many of us, and to support each other and hopefully more folks will come. I just heard that right across the parking lot at the same time is Joy Harjo and Black Belt Eagle Scout. When I read that, I was like whoa, at the same time, right across the parking lot! Then I was like, oh, man, I hope people want to come over. But then I started thinking, no, again, we’re in an energetic collective.

They are two of my most favorites. Joy Harjo lives in Tulsa, and I’m a huge fan. We haven’t met. I was trying to think of a way we could get her over to play some sax on a song. We’ll see. She’s such an inspiration for opening. She opens and talks about the guides coming in and, you know, she gave me a lot of permission for normalizing and just letting them come through, because that’s what she does. She talks about that in her memoirs.

We all love each other and are allies to each other. To be here at home preparing in the very place, in the very state where I had the wounding, is where I’m doing the healing for myself and others.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

Then Black Belt Eagle Scout, being one of those amazing bands. KP being one of those amazing artists who is Native nuanced with more post-punk. Just super cool. We have the same cinematographer, Evan Benally Atwood, an Indigiqueer and amazing artist. They were my cinematographer and editor on my video and have made some of Black Belt Eagle Scout, so it’s just a big party. I know Indian Market is like that and so it’s really exciting.

Like I said, my mission was to make an album that I like to hear and that if one person hears it and stays alive, mission accomplished. The guides are saying it’s bigger than that so hold steady and put in the work. Every day I’m working. It’s to the point where life is like, can we have a vacation at some point? I’m like, yeah, maybe we’ll spend a few extra days in Santa Fe [laughs]. I’m like, oh, people like this, let’s just keep going, make it bigger, you know, launching it. So it was perfect when we were thinking about when can we launch this?

JORDAN: Most people know this, [but] before I came to NDN this is what I did. I traveled Turtle Island and Indian Country as a hip hop artist and a workshop facilitator, invited into different schools and working with our youth. I’m excited to do this. Y’all are important to me. You get to see me at work as I show up at work. It’s something really different showing up on stage, but still the same in a lot of ways. I hope to bring just some really good energy.

There’s definitely a lot of energy that I bring onstage, but it’s also looking at my set as I put it together. There’s moments where I’m sharing some really upbeat songs, and then there’s moments where I’m sharing some songs or I’m asking you to take a moment to heal with me. Then there’s moments where I’m just being thankful and showing gratitude for all the love that I’ve gotten throughout the years for being a performer.

My main objective is just connection and really hoping to speak to our youth. So, there’s lots of songs about me being a father, there’s songs that are dedicated to our Indigenous youth, there’s songs talking about addiction, there’s songs about hope. That’s what I hope to bring to the Radical Imagination Experience. I’m excited, I’m truly excited to perform and show up as Mic Jordan, the hip hop artist, this fictitious superhero that I created when I was a kid.

[The name], Mic Jordan, is a super important one to me because of that character that I built for myself. It’s really a story about manifestation. I manifested this ever since I was a little kid, when I was super lost and I didn’t have role models. I didn’t have dads who were there or uncles. I had posters of hip hop and music. I had Michael Jordan posters on the wall. I had this little boombox that saved my life. It was my way of surviving.

I thought, when I was going through a rough time and I really wanted to do music, I was so scared, I [thought] I got to do something to save my life. I became, I created, I wrote it down, I manifested it, I closed my eyes and I pictured being on the stage in front of thousands of people performing as this guy named Mic Jordan. And I did it. I traveled the world. I perform next to some amazing people.

I was at the White House spittin raps and rocking on stage with Dave Matthews. But more so, I was talking to all these kids. I was walking in schools and I saw a mural made of me with like hundreds of 8 1/2 x 11, sketched out drawings, a picture of me in Red Lake. That’s the stuff that I really manifested. There’s a lot of purpose with what I’m doing with my music. I’m so glad I get to show up at NDN [Collective] to bring that gift.

Will your performance piece at the Radical Imagination Experience be interactive?

DAKOTA: That’s really a great question. The last festival that I presented at, I insisted that they bring people close to me and that I don’t do it on a stage. That people sit around in a circle. They had a similar question, because part of it is that I unfold this altar and then the altar folds out for directions and each of the directional cloths are like three meters long. So of course the tech team was like, well, what are you gonna do if somebody is in your way? I’m like, exactly, that is the question. It’s not just a question for me. It’s also a question for them.

One thing that I’ve done for this piece and for others is asking the question of, what are you going to do if somebody is like performing, or channeling or like sharing a message or a story through their body and they start rushing towards you? What is your response to that? What are you going to do if it’s somebody’s turn to share something and they’re chanting for 10 minutes straight? How are you going to respond? For me, as a creator, I’m really interested in that question because I don’t actually believe in the idea of an audience.

I think that the idea of an audience is based on a Western worldview where there’s some people that get to be actors, as if some people get to have agency and then everybody else just sits and watches and waits for the things to happen. Because we’ve grown up in a Western world, most of us, I should say, because most of us have grown up with these Western worldviews so deeply entrenched in us, once we get into a theater or into a show, oftentimes we fall into those cues.

We’ve done a version of this piece with two other people and we created this installation space that you can walk around, change your viewpoint, and start dancing with us. It’s really hard for people to take you up on the opportunity. The question of is it interactive or not, you know? Because of the time and timing and everything I probably won’t set it up in that same way that I’m describing it to you right now.

This is a question that I have for people. If you see somebody setting up a ceremony do you give yourself permission to interact? If you do, what is your protocol for engagement? Some people have asked, are you just going to give people permission to go up and touch stuff on your altar? And I’m like, Well, that’s not what I said. But if somebody was so bold to do that, then we would meet. We would meet that moment with the same question, what do we do? That’s also why I think about my work as Indigenous education. I really try to set it up for people. We are all actively creating this moment. Decide how you want to enter and engage and keep deciding.

How are you preparing physically, emotionally and/or spiritually for your upcoming performance at the Radical Imagination Experience?

DAKOTA: To be honest, I’m a little bit behind on my physical preparation. I’m kind of going through a season of my life. I think that it has a bit to do with my new job, but my relationship to my physicality is really different.I’m trying to stay committed. I’m also preparing the prayers and preparing the conversations.

My community is up against a lot right now, like we all are. We’re experiencing hyper militarization. A few years ago, the military clear cut 600 football fields of limestone forest. They’re slated to open up a firing range there, which is over our aquifer. We just found out last month that they’re also planning to build a 360 degree missile defense program. It’s experimental technology, but they’re not telling us that. They’re just scaring the shit out of people by being like, well, we need to build this in case China decides to bomb us, you know? Some of the people in our movement are highlighting this, saying, actually, this makes us more of a target.

One of the things that I’m preparing in my mind is very intentionally asking people while I’m there, can you help us? With your prayers, with your wisdom? Can you make a commitment to come and put prayers down here? Like, have you ever heard of a ceremony to stop war? I say that with a cheeky smile, but I also know that there are stories of that.

I also know that it’s not as simple as, yes, of course I will come to the ceremony and that will stop the war. That’s not exactly how the spiritual reality works, I think. I mean, the little bit that I know, but that is also part of my preparation is knowing what my community is holding and also knowing that the answer is in ceremony.

I’m going to be there for like 72 hours or something. I’m like, well, how can I use that time? Besides the preparation for this to meaningfully engage with people around, I’m also holding the very real reality that there might be a war, another World War, and that my people are actually in the crosshairs right now.

Marx will also be debuting their project at the event, and shared more on the preparation for both the performance and project release.

*Trigger Warning: Marx’s following response addresses suicide and suicidal thoughts please proceed with care.

MARX: So many moving parts right now. I really like that 12% of the grant goes to self care. In the midst of all the excitement and all the joy and all the opportunity, I’ve been reliving a significant amount of my own hardship from when I was younger. There’s a lightning theme in this. I’ve been here, with my parents right now where I grew up on the reservation and these huge lightning storms have been coming through and I’ve been paying attention and going and being with them.

When I was 20, I was suicidal. I was a suicidal youth. I was really taking a lot of risk when I was living in Oklahoma City. I was witnessing a lot of death in my community from the AIDS crisis and I was quite lost. I was out one night, super messed up in a storm outside. The building I was leaning next to got struck by lightning. So the lightning struck the house and knocked me out into the yard there. I looked up and there was this purple lightning storm, and I heard a voice that said, ‘stop killing yourself. You’re here for a reason.’ This big booming voice just reverberated through me.

It was Wah’kon-Tah, our word for Creator and God. It translates as the great mystery in Osage. Wakonda, no gender to that. It’s a great mystery and Creator, and I feel like it came through the lightning and told me. That was one of my first strong points of guidance. I’m guided by the lightning a lot of times so I’ve been paying attention to this season we’re in right now and I just love it.

I left Tulsa and I came out here where it’s quieter for me. I have my new stage piano. Also, my childhood piano is across the fence over at my parents house so I go and I play my childhood piano too and I sing to my parents because my parents are total allies. That fan you see Silas hold, it’s important to me. I spoke a lot about how I was ostracized when I came out in the eighties, but my family has grown and evolved and decolonized themselves as far as their spirituality. They’re allies. My mom gave me that fan when I turned 40, that fan that Silas holds. I’m holding it in part of the video and Silas holds it up. It’s kind of like a little star of the video, because that’s a gift to me from my mother, which is a gift saying, I love you and I accept you.

We all love each other and are allies to each other. To be here at home preparing in the very place, in the very state where I had the wounding, is where I’m doing the healing for myself and others. That’s how you could say I’m preparing right now, and a lot of singing and other details.

Erica Pretty Eagle’s making my album art right now. I’m like, put more of this, and she’s like, okay. And I’m like, less of that. She’s like, okay. She’s been so patient with me. All the visuals, all the story, all the message, all the publicity, all the things, we’re just really doing all the busy work. But also, I’m laying down tobacco and I found a hawk feather last night. The hawks are coming. One landed out there and talked to me last night.

As we prepare to pack it up and drive, we’re going to drive from Tulsa to Santa Fe next Wednesday. The main word I think of in Osage is ah.wash.kan, I’ll do the best I can. I just keep having to tell myself all I can do is the best I can do each step of the way. That’s a grounding point for me. That fan symbolizes that love of my family and my mother specifically.

As I sing that song about leaving here, that’s a very personal song, ‘Leaving Here’, the deer, the fight. In Oklahoma when you go home, people, they don’t say goodbye, they say, watch out for the deer. So that thing of being so vulnerable as a young queer, Indigiqueer youth, similar to a deer on a reservation highway at midnight with the storm clouds. All that depiction is very personal. My grandmother’s road is real. That’s all real to me, the city and how I survived there. All that song, very personal.

So, sort of dance it out and sing it out and have a video, all the vibes. It’s really exciting. It’s very healing for me to bring that back. Also, Sinead O’Connor having passed this last week, I have a deep connection with that, her heritage. She had trauma, but she sang about it clearly. I’m really feeling her energy too, helping me carry on and stand in the light, in the visibility and sing the songs and talk about where they come from. The pain and the healing. Hopefully I can deliver all that too.

You mentioned that you had to leave your community for the safety found in the city. Do you feel as though this is an experience that Queer Two-Spirit youth are still facing today?

MARX: What inspired this project was, you know, working as a therapist andseeing theTrevor Project put out a statistic, 33% of LGBTQ Native American youth attempted suicide in 2020. It’s the highest demographic of all marginalized communities.I wasn’t surprised, but I was shocked and I was stunned and I was inspired right after. It was almost like, Wah’kon-tah, Creator, was guiding it, because right after that I saw the NDN Collective Radical Imagination grant application.

I wrote passionately to NDN Collective and said, I want to take all my lived experiences as a therapist, an Indigiqueer person and an artist and do something. I don’t care if I make something where only one Two Spirit kid hears or sees it and they love themself and stay alive. Mission accomplished. I never thought they’d say yes, but they did and so it’s been almost three years of navigating. Once they said yes is like, oh, now I gotta do it. That’s been the journey.

Do I think that’s still an experience? Well, hell yes. When there’s 33% of kids attempting suicide, yeah, I guarantee you, some of them are not safe at home and not feeling loved and you know, bullying. Then we bring in all this anti-trans legislation. I tell people, gender diversity is nothing new. It’s very old. It’s just the way that we express it that’s new through pronouns, through the technologies of surgery and gender blockers and hormones and all that.

We have this technology. We didn’t have that technology back then, but we still had gender diversity. Maybe we didn’t have singular use they/them pronouns or have they/them pronouns, although I kind of am gender spectrum-y. I just land there to make people think harder. That’s a new way of expressing a very old thing.

In Osage, we have this word, Miixóke. Miixóke means a man guided by the moon, the moon being feminine, guiding man. I’ve been in conversation with our language department about this. This is a word that can be used across the gender spectrum for different reasons. Winkte in the Lakota, you know, Nadleehi in the Dine’. So this is very old and so this legislation, all this blowback about this is new, it’s a fad. It’s not new. Colonization is not new either. We’re still in it.

I made a music video of this song, How long? I just feel like so much of this has been guided because we filmed that video, the narrative part of it, in two days with this amazing community of people that just showed up that day and the few protagonists that I did bring in specifically. I was living in Portland, filmed most of it in Portland, the church scene and the scene in my house. There was motion portraits of contemporary Two Spirit people in their regalia. I came to Oklahoma and I was very passionate. I wanted to film the whole thing here, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it.

So I came and I said to people, send me portraits of yourself and they responded, no, I’m busy or I don’t want to. What are you doing? So I came here and I traveled around and I thought I would just be taking portraits of people, but I heard everybody’s stories. So to ask me, do I think it’s still a lived experience of people to not necessarily feel safe? Yes.

Creative communities are all around the world. No matter what your heritage is we all have that earth-based tribal Indigeneity from around the world.

Marx Cassity (Osage/Kaw)

I met one young Cherokee, Indigiqueer person who’s in medical school in Tahlequah, who’s one of the motion portraits, and not that long ago they came out to their parents and their parents didn’t speak to them in their own house for almost two years. They were the age of 16 or 17. To hear that story and to see that person now being in med school and advocating for trans children in their work, it’s absolutely true that people are still being ostracized and not safe So, we have work to continue.

I love the Land Back Manifesto. I love the idea that under the Manifesto we talk about land and culture and medicine and education and all the different factors under there. One is relating and kinship. Under that I would say gender and sexuality are part of The Landback Manifesto. That is, we are colonized in that, but we’re doing the work here.

People my age and older are still not necessarily out and coming out and feeling comfortable in some of the places they live. It’s very vulnerable to be here saying, shine the light on me, but I do because they are the ones who came before me and did that and are the ones who helped me to stay alive. I almost died in the midst of all that, but I had those points of light along the way, helping me.

We’re working really hard to get the new album out to a lot of people. I’ve gone beyond what I ever have done with an album release. I’m just working really hard, getting the best publicist I can find to help me. I’m really going for it. Part of it is some inspiration around the music or people hear it and they like it, but it’s, you know, I’ve been doing that a long time. This is more. I’m on a different mission, and it’s keeping me showing up more, talking more, calling out more and putting myself out there more. Like I said, if even one more kid, one more person gets inspired, great. Even if they think they can do something better than me, like, I can do that better. I can play that better. I can sing it better. I say, do it!

What is a project that you’re currently working on and how was it born?

DAKOTA: The project that I’m honed in on I named after the form that brought me into relationship with hip hop, which is my Mele. Mele started as me making a solo work and then realizing that I need to find ways to bring the community into it. The process came from reflecting on, what’s my creative journey?

A few months ago I had the opportunity to present this work to the community here in Guam for the first time. It was really interesting because the work in a lot of ways is about being born and raised in another land and having all of these different cultural lineages, creative lineages bring me back home. Coming home with a different set of gifts than I was given. Not that I don’t have those gifts anymore, you know?It’s not that I don’t have my ancestry. It’s just, I have more. That’s the work that I’m going to be presenting as a part of the event in Santa Fe.

What I love about it is it came to be because I was asking questions about how my ancestors would see the world, how my ancestors would see me. How would they recognize me as a part of that, you know? The way that I did that is, I looked towards the traditions of navigation from our region. There’s this navigation technique which is called Étak. It’s knowing where you’re going by knowing where you came from and then knowing an island off in the distance. So you find the third point by knowing where this island is, and you’re here, but you know that you came from here, and so you track. In Micronesian navigation, you don’t move through the water, the water and the sky move around you. So you track the movement of these two islands and then that helps you know where this island is moving, how it’s moving.

The cultural dance script I told you about, it’s got a weird story, which is that aunties learned Polynesian dance and they just started using that language and choreographed to CHamoru pop music at that time.That was what I understood as cultural dance. That’s the second island on the side. That second island for me has also been hip hop. It’s also been Danza Mexica . It’s also been house music. It’s also been my relationships to Swinomish and Schwdab f elders and the little bit of understanding that I have about Coast Salish lifeways, from those relationships. It’s also been indigenous contemporary dance. It’s also been my relationship to Maori folks, Aboriginal Australians, right? The piece involves me, unfolding an altar. That is an acknowledgment of all of these different spaces and places and ancestors and energies.

The purpose of it for me honestly keeps changing. I keep collective liberation at the heart of my prayer, you know? But I think I’m starting to understand more about what this piece is. In some ways, it is like a prayer of gratitude, but it’s also a prayer of the journey to know oneself. What’s interesting, is even just now, talking to you about it, that third Island is like all of these different art forms. By the end of the piece, that third island actually becomes me.

One thing that I’m kind of noticing is the heart of the prayer, that we can all know who we are. I don’t mean that we can all know what nation we came from and what language, although that may be a part of it or it might not be. When I say we know who we are I mean, we know who we are in the Creator’s eyes, right? We know that our ancestors have passed us gifts and purpose and we have this support around us to hold those gifts and to fulfill that purpose. So, I think that that’s part of what the prayer is becoming. What the piece is becoming.

The project to me is iterative. It’s different in every place and this is just one aspect of it. This is the solo exploration of it. This is me. In December, there’s going to be another iteration of it that involves 12 other CHamoru artists. I’m actually thinking about Mele as a creative research project. My hope is that this way of thinking and creating can be of use to my people. That it can be a way for us to reclaim our relationship to who we are, to reclaim our ancestral worldview, our lifeways. That it can be of use for our creative community.

I was still asking that question of how does a Matao person create? For what purpose? What traditions do you draw from? And it kind of goes back to that. What we know about our culture, cultural dance and song, by and large, with the exception of a very small but significant amount of cultural material, was created from the eighties forward. I don’t know if you can relate to this, but imagine that you didn’t have references for creating what we call traditional art.

For me, I’m not trying to create a representation of tradition. I know that inside of traditional practices, there’s entire universes that steward health and wellness for the community. So that question of, well how do you create that out of what you’re going to be is what was driving this piece. My initial way of trying to answer that question was, I need to explore my own genealogy, Right? When I say genealogy, I mean that ancestrally, but I also mean that culturally.

Another Micronesian navigation technique is that you’re going from one island to the next and that you chant the entire way. But the chant is actually a recitation of genealogy, but also of ecology. As you’re chanting, you’re saying the names of ancestors that are literally below you in the ocean or are flying above you as birds or there’s certain currents that you’re entering or there’s certain corals. That’s when I thought about myself as an indigenous person, as less land based, which might sound so wild to a lot of like native peoples, but like more celestially.

I started to wonder, well, maybe the coral that is supposed to be at this place when going from one island to the next is not coral, but it’s like Hawaiian dance. Then, the next piece of that was hip hop. And then the next piece of that was Danza Mexica , and then the next piece of that was breaking and capoeira, you know what I mean? So, my theory was what if I compose a chant?

There was also a version of this I called an untraditional Micronesia navigation chant. If I could compose a chant that can take me from the beginning of where I’m at and I recite this genealogy, eventually, I’ll get to where I’m going. In some ways, I don’t know what the end of the chant is. This piece has gone from being 10 minutes long to 20 to 30. The latest iteration of it was about an hour and. I’ll be presenting like a 30 minute version of it in Santa Fe.

What was one of the first albums that you bought that you can remember?

JORDAN: My mom was cool because she never censored music, so she was buying me things most parents wouldn’t buy their middle school aged kids. Doggystyle, Snoop Dogg came out, Gin and Juice, Lottie Dottie. All those amazing songs. She bought me Nirvana Nevermind. I was blown away by In Bloom and Lithium and Come As You Are.

I was this hip hop kid who was very much into hip hop, but I still loved grunge music, too. I was probably rocking a lumberjack red and black shirt and then when I heard Biggie, “with the red and black lumberjack with the hat to match,” I knew I was okay with my sense of style. So, when we’re talking about blending music, that was one of the first albums that my mom bought me was Snoop Dogg, Gin and Juice, and Nirvana Nevermind.

As you shared, your musical journey started as a way to work through trauma. How has that evolved over time?

MARX: I remember being three years old, out here with my Mom and my aunties with a vinyl record, and it’s Johnny Cash. It’s probably 1970 or 69. I’m little, I’m itty bitty and I’m singing into my thumb and I’m singing a Johnny Cash song and my aunties are just clapping. My aunties would bring me and play the Beatles. Out here on the Osage Rez, they’re into just country music, like classic country music and all that. I was always entertaining. They were like, you are just an entertainer! You came in doing this. So, I just continued. I’m just kind of built that way.

I still get nervous when I’m on stage but I’m always inspired to get up there and try it again and keep going. Over the years when I was trying to sustain myself with music, it was really hard to be a full time musician. I would drop out of nursing jobs and go on a tour for a few months or travel around and play living room concerts. I had a lot of touring of small venues and places like hot springs. All the people come out of the hot springs and they’re all laying down.

Those are some of my favorite gigs, when people are just really quiet after they’ve been soaking. It’s so much more medicinal, you know, and then a lot of more conscious community or hippie kid gigs. Played a lot of Earth Day Festivals, steeping in musical consciousness.

Just that inspiration, talking about how what if our best days are ahead of us? Nobody romanticizes our histories better than us. People are really good at it, including us.

Dakota Camacho (Matao/Chamoru)

Creative communities are all around the world. No matter what your heritage is we all have that earth-based tribal Indigeneity from around the world. Folk music and storytelling and singing is something we’ve always done to help us be here in this existence, which can be hard, you know? So, I think this is very old technology. We’re just doing it in a new way to reamplify it all.

In mainstream media, sometimes when they’re interviewing me about transness, people really want to understand it. I think they don’t know how to talk about it. So I’m really trying to help mainstream journalists allies. They’re very supportive, but they don’t understand on a deeper level, the indigeneity, the ancient way.

Then the racism and colonization that came in and erased that, just like so much else. We have to help non-Native journalists understand all that too.I think they’re starting to catch on a little more. I’m really trying to drive that home with folks. All those old ways of being that have helped us be here, music, ritual ceremony, medicine.

My wife is French. I go to France, I’m like, this is old. We had gone to Rome and that stuff was all B.C.. Our ancient history here is Native. The United States of America? Tiny on the timeline and people say, oh, yeah, that’s ancient history.

Where did you learn guitar?

JORDAN: My grandfather used to always have a guitar and he plucked it around every now and then. It was just kind of always back there, always sitting in the back and it collected dust. But when he pulled it out, it was probably where he was. He was in a good mood and kind of feeling like it was almost like [a] spiritual transaction. His spirit was called to grab that guitar, and that was the same with me. I was self-taught. When I always hear, “You’re so talented,” which is such a nice thing to say, but I don’t think I had talent. I think I just had grit and persistence and I played till my fingers bled. No joke, I really did.

Then there’s moments where I’m just being thankful and showing gratitude for all the love that I’ve gotten throughout the years for being a performer.

Joradn Brien (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe)

What learnings did you take from your Radical Imagination project?

Dakota’s project entailed working towards creation of FANHASSO, an Extended Reality (XR) app as a tool to strengthen Matao/Chamoru imagination muscles. The app allows people to use their smartphone to see into the imagination of Matao/Chamoru people.

DAKOTA: What I found out through that process was that I’m going to need a lot more funding and a lot more time to bring my vision to life. So, it’s not on hold, it’s a part of the bigger project with these 13 artists.

Can you share more on how the Radical Imagination Grant has nurtured your project and vision and are there other individuals or groups who have supported your artistic endeavors?

MARX: Thank you for that question because it opens up this whole other when you ask about my influences and how I write and all that. My worldview and the way I see it in my reality is that I have ancestors and guides who are informing me a lot of the time. When I got the NDN Collective grant I started writing and holding it all and thinking about it all.

Then Nick Tilson spoke, and then he spoke again. It came just at the halfway point. He spoke again and I started realizing, when he talks,I just ugly cry. The second time he spoke I was just like, okay. I was inspired to keep going by him sharing about the buffalo and how in the buffalo, when a storm comes, they go into the storm. He was like, I figure y’all are probably in the storm right now being halfway through your projects, and I was [laughs]. Oh man I was.

Just that inspiration, talking about how what if our best days are ahead of us? Nobody romanticizes our histories better than us. People are really good at it, including us. What if our best days were ahead of us? That vision and that visioning, both of those inspired me to write the second verse to a song based on Nick’s words.

After that I started realizing, I was getting a lot of wake up calls around 4 a.m.. I would be woken up and I’d be given song lyrics, melodies. I would receive them. At a certain point I started saying to what I felt like were guides and ancestors and trancestors – I was like, why 4 a.m.? Can’t I just sleep in longer? They’re like, no, this is when you’re quiet [laughs].

So unless you cultivate being quiet more later in the day, it’s going to come at 4 a.m. That’s when the veil is thin and so for a long time I was like this this material is just coming, flowing through, channeling through so much like and I realized at a certain point

I believe that this is all the prayers of NDN Collective and Nick and his lineage and the team of people who put this all together, all of whom I don’t even know. It’s the energy of all of that. That’s the intentionality and I started being really grateful to my own guides and ancestors, but also anything that’s coming through from those prayers. I think it is specific to NDN Collective. I mean, every interaction I’ve had with people. We went to New York last year and a lot of the NDN Collective team were there and it’s just been lovely.

As an artist, as a Radical Imagination artist, I just feel like the actual people in the energies and the prayers and all the intention has flowed through and it is a big part of what this project is. I mean, the fact that I saw that statistic and then here came the grant and then they said yes, that’s just all that intentional prayer work that we’re all doing and I just feel like we just met up along the path together.

The intention behind Radical Imagination. Nick saying he believes that our artists, the ones that create, there’s a technology to that, a spiritual technology to that. The creativity and the artists are the ones who bring it to the next level and I’m like, right on man, I want to join that mission.

Osage Nation Foundation is another backer of mine who gave me a grant. I’m so proud of my own Native tribe, providing grants to artists. That’s no small thing, so I like to mention them. I am proud of that.

My grandfather was a cattle rancher and he had a 9000 acre cattle ranch on the reservation. He privately owned it and all the mineral rights below the land are owned collectively. The oil and the water and all the minerals. It was allotted, so in the allotments in 1906, my grandfather owned 9000. Before he died, he gave that back. He gave land back, the entire 9000 acres, back to the Tribe. It’s one of the largest grants that I can find of land, that of a private entity giving it back. He’s Osage himself and gave it back to the tribe. That’s a version of my inheritance. It’s an active cattle ranch. It’s quite valuable. My aunt still has the cattle ranch and now she leases the land from the Tribe and that money goes to the Foundation and that Foundation money goes to artists, so it’s all full circle. I don’t know if that’s important for what we’re doing here, but I’m really proud.

Any way that a Native nation or people can find to grant their artists, I think you should and follow Nick Tilson’s words on that. There’s a spiritual technology to that, that’s very important. Also, people donating to NDN Collective and Osage Foundation and all these types of places that provide grants to artists, that’s vital as well to keep this going, because we need it as artists. We need it. It’s hard to be in the art industry.

Our Congress cut those grants and the Foundation has to go through the Congress. That’s why I’m trying to put this out there. This is important. If I can do anything to support the Foundation, you know?

We are so thrilled that we had the opportunity to interview these three performers and look forward to their performances at the Radical Imagination experience in Santa Fe later today. We hope you can join us!

For those tuning in from afar, NDN Collective will also be live streaming the event on our Facebook and YouTube pages.

Related Articles

Blog | Taking Our Ancestors with Us: Two Artists Cultivate Community Awareness Through Transformative Art

Blog | ‘We Are Here!’: Indigenous Art and Expression from Opposite Ends of Turtle Island

Blog | Community, Salmon, & Water: How Indigenous Illustrator Jackie Fawn Creates Art for the Movement

Press Release | NDN Collective to Hold Free Event Focused on Resistance & Art

Blog | Announcing NDN Collective’s 2022 Radical Imagination Artist & Storyteller Cohort

Blog | NDN Collective Kicks Off Radical Imagination Virtual Festival, A Multi-Day Event

NDN Live | Radical Imagination Virtual Festival

Blog | Announcing NDN Collective’s 2021 Radical Imagination Artist & Storyteller Cohort

Blog | NDN Collective Selects Ten Indigenous Radical Imagination Artists From Across Turtle Island