Trigger Warning: This blog contains words, images and video displaying acts of police brutality/state violence against Indigenous Peoples. Please proceed with care.

Between 1854 and 1855, a few years after Washington Territory was separated from Oregon Territory, an important chapter in the region’s history unfolded. The Washington Territorial government, through Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), was in the process of signing a series of treaties with local Native American tribes, a move designed to force these Indigenous communities to relocate to designated reservations and open the land to non-Native settlers. One such treaty was the Medicine Creek Treaty, that included my own tribe, the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, along with the Nisqually, Steilacoom, Squawskin (Squaxin Island), S’Homamish, Stehchass, T’Peeksin, Squi-aitl, and Sa-heh-wamish tribes. The treaty was signed on December 26, 1854, near Medicine Creek in what is now Washington State.

Within the historical framework of land treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government, a critical provision in these treaties required the tribes to make a profound concession. This entailed giving up a significant portion of our cherished ancestral territories, which ultimately led to our relocation to designated reservation lands. This pivotal loss played a critical role in enabling and accelerating the westward expansion of American settlement during this transformative era in U.S. history. The tribes in Washington State found themselves in the same challenging predicament.

While recognizing the tribes’ concession of land, the Medicine Creek Treaty also sought to protect our basic rights. It explicitly recognized our continued right to fish, hunt, and gather resources on the lands we retained and emphasized our “right to take fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations.” The treaty’s “right to take fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations” is significant because it guaranteed Indigenous Peoples’ access to fishing and hunting grounds they had traditionally used, even if those grounds were located outside their tribal reservations.

The right to fish became a unifying identity among the diverse tribes and nations of Puget Sound.

By the 1890s, salmon had become a valuable commodity to non-Natives, and pressure was mounting on the “usual and accustomed grounds” that Native American negotiators had reserved for tribal peoples in the treaties. By the 1960s, salmon populations had declined significantly due to unregulated commercial fishing and the construction of hydroelectric infrastructure. In direct contradiction to treaty language, Washington state officials interpreted “usual and accustomed grounds” to mean fishing only on Indian reservations and they repeatedly denied Native peoples access to all off-reservation fishing areas.

Without the means to feed their families, many local Native Americans languished in poverty, but they refused to be bullied. The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, for example, sought justice through the federal courts. In United States v. Winans, 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the tribes’ treaty rights to fish on their usual and accustomed grounds and stations, including those off-reservation. Washington State, however, ignored the federal courts and worked to dismantle the federal law. Rather than accepting injustice, the tribal nations chose to take a stand, and so began the Pacific Northwest’s Fish Wars.

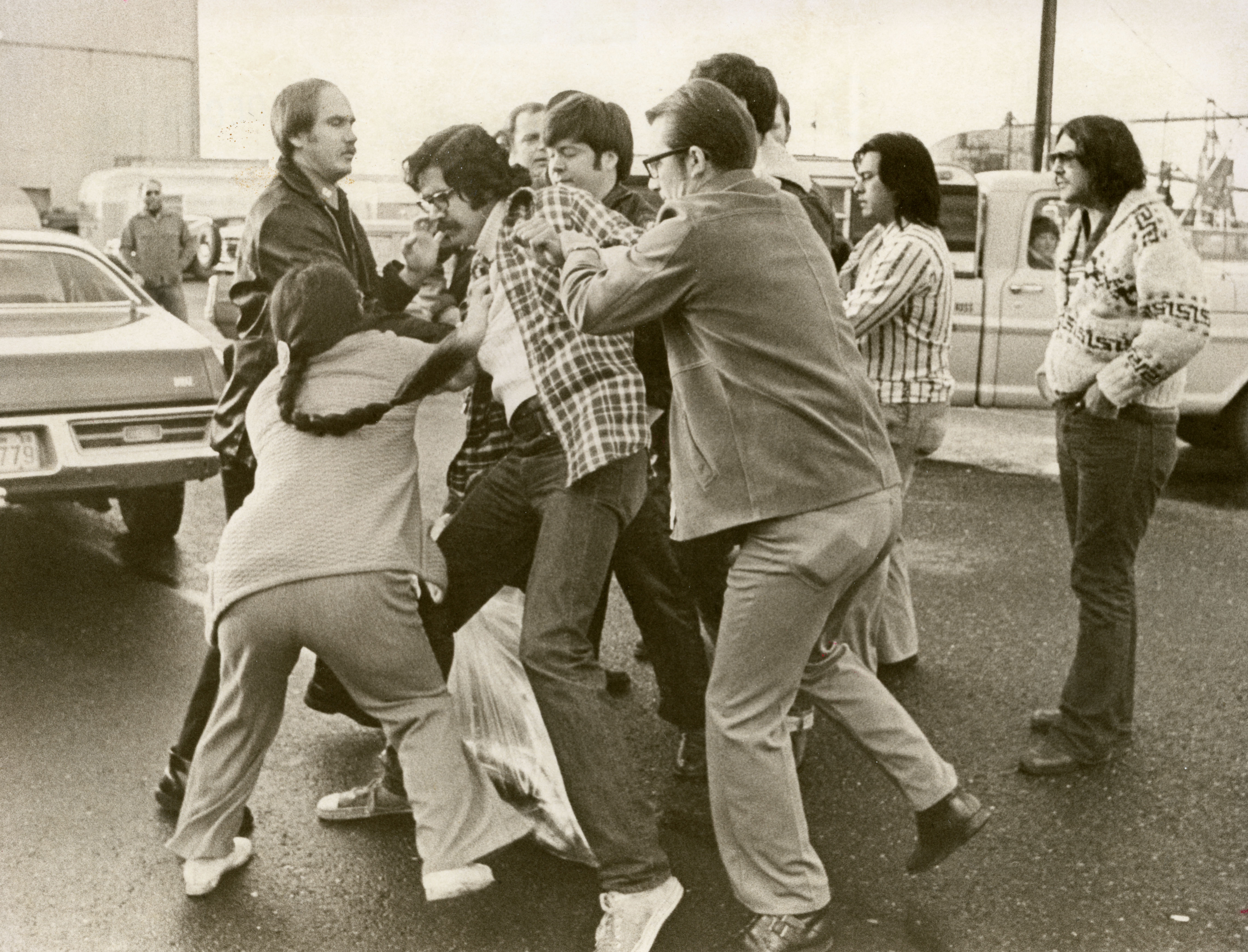

Trigger Warning: The below image contains acts of state violence against Indigenous Peoples.

In the early twentieth century, Native peoples protested the state’s illegal fishing regulations by simply continuing to fish, thereby exercising their treaty fishing rights. Because the U.S. Constitution defines treaties as “the supreme law of the land,” tribal nations throughout Washington also filed lawsuits against state officials for violating their treaty fishing rights, but the state continued to violate the treaties. The decades-long Fish Wars gained momentum in the mid-1960s. In the homelands of the Puyallup, Nisqually, and Muckleshoot tribes in the central Puget Sound region of Washington State, Native peoples of all ages risked everything to force the state to uphold the treaties. The tribal members persisted despite being threatened, harassed, clubbed, tear-gassed, and imprisoned by state officials.

The late Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually Tribal member, environmentalist and treaty rights advocate, emerged as a key leader in the “fish-in” protests that unfolded during the Fish Wars of the 1960s and 1970s. Coordinated by the newly formed Survival of the American Indian Society (SAIA), a group in which Frank was a founding member, the fish-ins were inspired by the civil rights protests in the southern United States. However, they were adapted to address the specific issue of fishing rights and reflected Native American rejection of cultural assimilation. SAIA worked to reframe the history of Native American fishing rights arrests, extending their protests back to the 1930s.

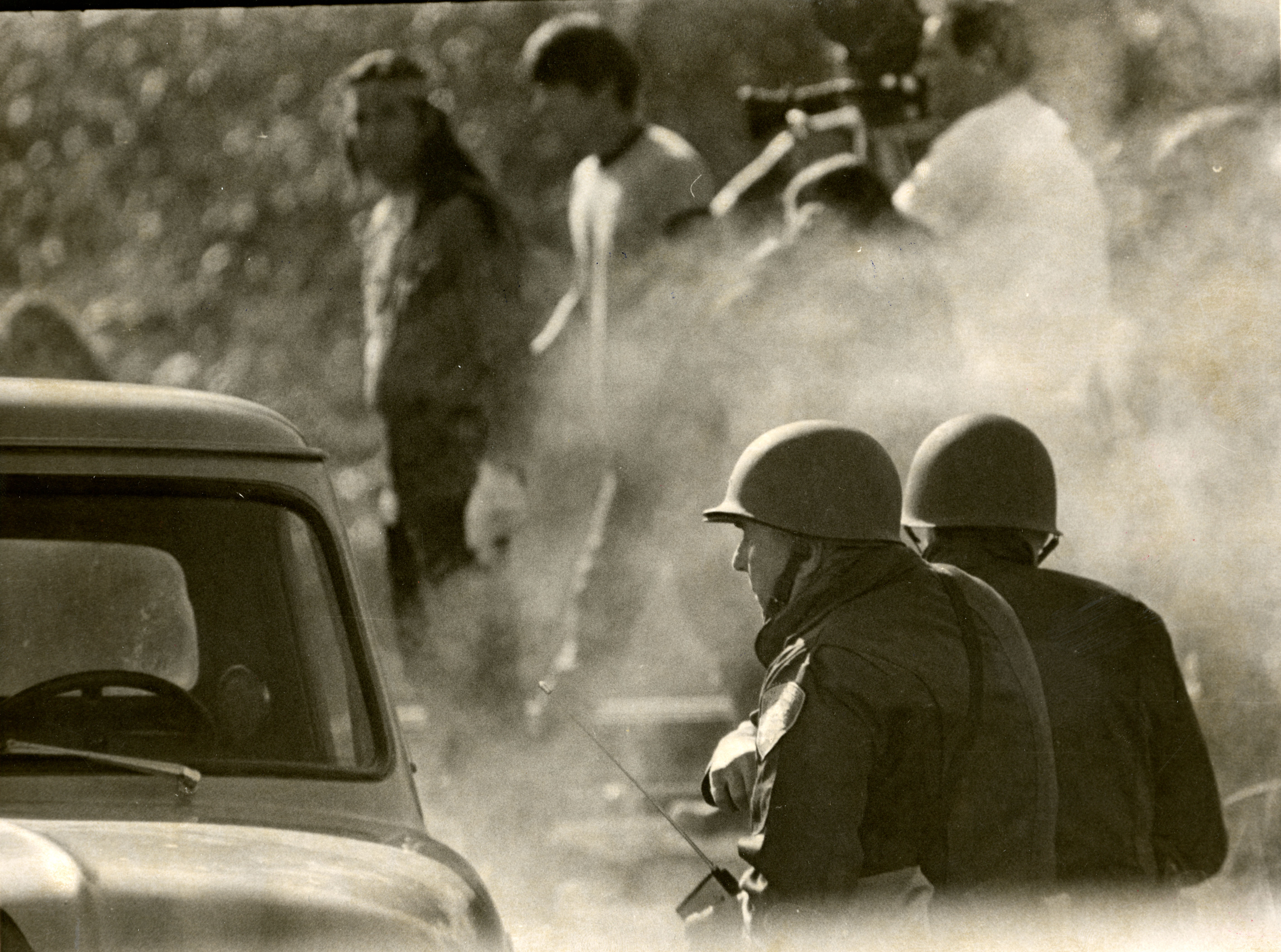

Trigger Warning: The below image contains acts of police brutality against Indigenous youth.

The leader of SAIA at the time was Hank Adams, a member of the Assiniboine-Sioux peoples, who was a prominent Native American activist who worked extensively to protect the rights and sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples. In late 1968, Adams became actively involved in the Fish War conflict, speaking out against federal regulations imposed on Native Americans fishing along the Nisqually River in Washington, including coordinating efforts with Frank Jr. and other allies on conducting fish-ins.

Newly formed groups adapted and orchestrated their own strategic fish-ins, which were well-planned and publicized off-reservation fishing expeditions designed to provoke arrests and keep tribal members in court. A combination of local elders and educated Native youth worked together to organize the fish-ins and other activist events. When tribal members fished for salmon and steelhead trout off their tiny reservations, they were subject to state law. State regulations prohibited the use of nets and traps, despite these being traditional Native methods of taking fish from rivers and streams. Native Americans who insisted on their treaty rights were subject to arrest and prosecution. The right to fish became a unifying identity among the diverse tribes and nations of Puget Sound, who were traditionally tied to natural resources rather than real estate.

Trigger Warning: The below video contains acts of police brutality against Indigenous Peoples.

In the documentary Back to the River, by Salmon Defense, Nancy Shippentower-Games, a member of the Puyallup Tribe and a close family friend, recalled a fish-in she attended on the Puyallup River, the traditional fishing grounds of the Puyallup Tribe, on October 13, 1965, when she was only twelve years old. “There were a lot of women and children there. All of a sudden my mother said, ‘Look!’ We turned around and these game wardens come out from behind the bushes, and these guys are big. They had these jet boats and they rammed our canoe. And then the attack was on. We were young and they were slamming people around. There was fear in my grandmother’s eyes,” said Nancy.

Another, more famous fish-in also took place on the Puyallup River on March 2, 1964. Inspired by civil rights sit-ins, actor Marlon Brando (1924-2004), San Francisco Episcopal priest John Yaryan, and Puyallup tribal leader Bob Satiacum (1929-1991) “fished” the Puyallup River without a state permit. Satiacum first came to public attention in 1954 when he was arrested for illegally fishing in the Puyallup River in Tacoma, Washington. Satiacum was convicted at the time, but the Washington State Supreme Court overturned the conviction. The action on March 2nd led to the arrest of Brando and the clergyman, although Satiacum was not arrested. The Pierce County prosecutor declined to file charges, and Brando and Yaryan were released. My grandmother, Dr. Verna Marie Bartlett, said of Satiacum, “His actions, alongside other activists, symbolized the resilience and determination of the Puyallup people during times of struggle.”

Trigger Warning: The below video contains acts of police brutality against Indigenous Peoples.

Another key figure in the fish-ins on the Puyallup River was Puyallup Tribal member Ramona Bennett, who joined the Puyallup Tribal Council in 1968 and was elected tribal chairwoman in 1971. Like other fishers of the time, she and others worked to set up a camp on the Puyallup River in 1970 to exercise their treaty rights to fish the waters. The Puyallup encampment was located near the Pacific Avenue Bridge in Tacoma, Washington. At its peak, the camp housed several hundred people in tents and teepees.

They came from all over. Many were active in the Native rights movement elsewhere. Eventually, the local police chief warned them that if they didn’t leave, there would be a raid. The protesters stood their ground, as seen in this video footage of the camp and the subsequent raid. Bennett says she remembers looking up at the old bridge, where dozens of officers had lined up with their guns. “The green bridge looked like a porcupine,” she says, “they were lined up along the railing up there with their guns pointed right at us.” Shots were fired from both sides. No one was killed, but the protesters set fire to a creosote bridge. Bennett fought back when an officer shoved her. Sixty people were arrested.

In the end, she served no jail time. The September 9, 1970 standoff on that bridge in the middle of Tacoma would gain the attention of U.S. Attorney for western Washington, Stan Pitkin, who was present to witness and experience the violent actions of the state, having endured tear gas. He would go on to file suit against the state for violating tribal treaty rights. Adams continued to work on the fishing rights issue, lobbying representatives in Washington. He compiled and presented information critical to making the case for Native American fishing rights in the legal challenge.

After four years of gathering information, Judge George Boldt issued a decision in United States v. Washington, 1974, that guaranteed and affirmed the right of Washington’s Indian tribes to act as co-managers, entitled to half of the fish harvest each year. After hearing from dozens of Native witnesses and reviewing hundreds of documents filed in the case, Judge Boldt ruled that “in common with all citizens” of the United States – the language of the treaty – meant “sharing equally.”

The “Boldt Decision” was controversial at the time it was made, as it marked the legal culmination of years of intense struggle and confrontation over Indigenous fishing rights in Washington. These struggles ranged from grassroots protests to violent confrontations and everything in between. The resolution of the federal government’s 1970 lawsuit against the state of Washington brought about a significant change in the management of fisheries in the state. It forced the state government to recognize tribal fishing rights and tribal sovereignty, effectively dividing the annual fishery harvest among tribes, non-tribal sport anglers, and the commercial fishing industry.

Although the decision was a victory in the fight to protect Native treaty rights, not all tribes benefited from the Boldt Decision. The Makah, for example, lost their ancestral halibut fishing grounds in Canada after that nation and the United States declared exclusive fishing zones that ignored Indigenous fishing rights. Non-treaty tribes such as the Duwamish, Chinook, and Snohomish lost access to all their usual and accustomed fishing grounds because the Boldt Decision applies only to federally recognized tribal nations. The non-Native backlash also intensified in the 1970s and 1980s, as sport and non-Indian commercial fishermen expressed resentment over what they perceived as the loss of their rights, even though those so-called “rights” had never been theirs in the first place. Tensions over tribal treaty fishing rights continue to this day.

The powerful legacy of the Fish Wars lives on strongly in my tribal community, and we have always held it up as a focal point for defending our rights as Indigenous Peoples. Many members of my own family have carried on this legacy. In my lifetime, my grandmother, great-uncle, and uncle were all Puyallup Tribal members who fished the Puyallup River to uphold their sustenance, livelihood, and traditional way of life. As a water people, the Puyallup Tribe, like other tribes in the Pacific Northwest region, have always fished our traditional waterways. Our connection to the water sustained our cultural ways, and we deeply revered and respected the life of the water for what it gave us, even viewing it as its own community with which we had a reciprocal relationship. They are part of us and we are part of them. This understanding continues to this day.

As we remember the immense sacrifices and courageous activism that took place during that tumultuous era to preserve our right to simply fish in our traditional waters, the impact is still very much with us. In 2019, more than 50 years later, the bridge and an older portion of the bridge nearby, where members of the Puyallup Tribe, relative nations and allies faced off with local law enforcement here all those years ago in 1970, had been renamed by the City of Tacoma in partnership with the Puyallup Tribe. It’s now called the Fishing Wars Memorial Bridge and in txʷəlšucid, our traditional language, yabuk’wali, which means “place of a struggle.” The renaming of the bridge honors our history, but also serves as a reminder of the critical importance of exercising our inherent right to self-determination as Indigenous Peoples. The Fish Wars was ultimately an Indigenous-led movement that defended our rights on our terms, demonstrating our ability, and power, to advocate for our traditional ways of life.

Learn more about the Fish Wars, treaty rights and the Boldt Decision in the C-SPAN video below

Trigger Warning: The below video contains acts of police brutality against Indigenous Peoples.