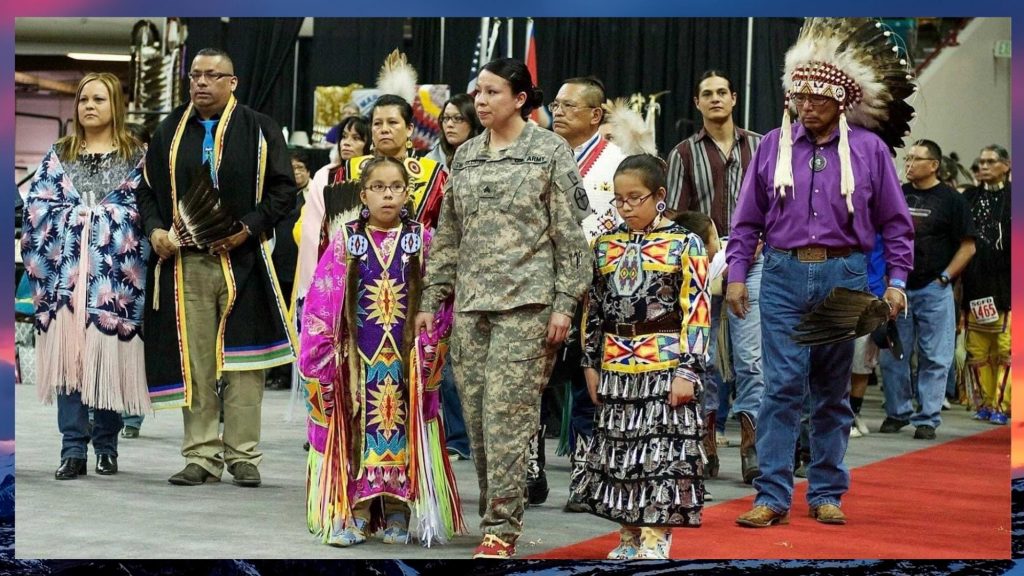

I served in the US Army Reserves for 8 years. During my service, I was deployed to Kuwait, where I gained so much experience, knowledge and skills. It is a very confusing thing to be both proud to be acknowledged as a warrior in my community and country and feel shame for having been a part of the violence inflicted by the U.S. military on Indigenous lands overseas — fully knowing its history of violence and genocide toward my own people.

Although Veteran’s Day marks a time for people who have served in the military to be honored for our sacrifices, I’m asking my fellow veterans to explore what it has truly meant to have served in the US military. I think about how the skills we learned in service — as well as the perceived commitment to making this country a safer place — can translate to true service to our communities and people at home more directly and with integrity. I invite others to join me in figuring out how we can put our knowledge, experience and skills towards community organizing, nonviolent direct action, and plugging into movements demanding systemic change.

My experience of being a woman, Indigenous, and a veteran is complicated, to say the least. The history of Native people serving in the U.S. military is long, and not accidental. During WWI, Native folks started enlisting at higher rates, because the U.S. government told Indigenous leaders if their sons enlisted, they could have their land back.

This hyper-militarization is not necessary, and is in direct opposition to the loving, equitable and just world that most of us crave so deeply.

While Native people are not monolithic, many of us enlist because we are the original stewards of this land and have the responsibility to defend it — even if it means doing so through the same military that attempted to eradicate us. But the reality is — through colonization — we were stripped of that land by the U.S. government in the first place, and they’ve held it over our heads to convince us to become part of their systems.

In addition to being stripped of our relationship to the land, we were also stripped of our traditional roles in a warrior culture that had existed since time immemorial. So, when opportunities arose for us to reclaim that warriorship, we took it. For so many of our youth, it is perceived that military service is the only path to stability and a better life, as opposed to the alternatives of prison, death or addiction — all of which are symptoms of the systemic oppression our people live with.

Despite joining the effort to defend U.S. soil for over 100 years, promises from the U.S. government to return our land have been empty. We’re still fighting for our land back today, and are often met with state violence from the military and police, for doing so.

This summer, I was arrested alongside 20 other organizers protesting Trump’s visit to Mt. Rushmore, for which he had not gotten free and prior informed consent from the original stewards as required by multiple treaties. As we rightfully defended our land, we were met with tear gas and rubber bullets by the local police and National Guard.

At Standing Rock in 2016, troops with experience in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan were sent out to terrorize the hundreds of people camped there during the harsh North Dakota winter in an attempt to protect our water and land. And this summer, as people in cities across the nation rose up to demand accountability for the continued murders of Black people by police, the National Guard and other unidentified military personnel were out in full force to deny people our right to demand change.

This hyper-militarization is not necessary, and is in direct opposition to the loving, equitable and just world that most of us crave so deeply.

We’re now in a critical moment for action, with a new president elect and a soon-to-be revamping of our cabinet. This is the time for veterans to be organizing and joining efforts to build a world where all people thrive.

This is a time for us to heal, find our next purpose and mobilize.

For me, serving my people and community post-military has meant using learned skills and knowledge to organize and engage other veterans and my community. It has meant healing from harms done to me while in service. It has meant reconciling being an Oglala Lakota/Northern Cheyenne woman and being used as a tool of US Imperialism. It has meant transitioning from a soldier who follows orders to a warrior who is committed to the well-being of not only my people and our relationship to the land, but that of all peoples.

This is a time for us to heal, find our next purpose and mobilize. Veterans can and should make up a powerful force to hold the next administration accountable. Together, we can work to get LANDBACK for Indigenous people, divest funds away from the military and police and towards public services that so many desperately need, end state violence and caging of children at the border, end military aid to oppressive governments, and overall serve our people in a way that moves us towards a collective liberation.